Against Lowercase

Ditching a literary convention as an act of self-service

Lowercase writing isn’t just a style, it’s a statement. In this essay, I examine what it’s trying to say. If you enjoy my writing, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. —FLD

Sloppy texters worry me. If they do not care to spell a word correctly or amend the misfire of a bulky, intruding thumb; if they fail to recognize when information is asked of them, explicit or implicit; if they forget to respond entirely despite the cell phone evolving into a human appendage, where else might their negligence extend?

I want to tell you—clearing my throat, straightening my bowtie—that I am bothered by one particular and intentional disruptor of good, well-intended writing. I see it in text messages, on social media, and in online articles here on Substack. I don’t yet see it in novels because traditional publishing is slower to fold, but I fear one day I may.

Writing exclusively in lowercase offends the reader’s trust. In school, we learn that a capital letter signals a proper noun, but more frequently, the beginning of a sentence. Between the punctuation and the capital lies a reprieve for the reader to rest and prepare again. Upset that balance, and the reader fatigues. She rolls on and on, nagged by the same low-grade disorientation as a run-on sentence, chasing down a hallway with no doors. Eventually, her mind aches. She abandons the page or arrives at its end resentful that she was not given proper care. I especially do not like looking at “i.” It was not meant to stand alone. It lacks command. Beginning a sentence with it is a hideous act, like placing a child at the frontlines of war, or stripping a man of his armor and asking him to march.

Errors in spelling and diction are inevitable, but choosing to write in lowercase is not a slip, it’s a statement. The lowercase writer rejects convention not for clarity, not for authenticity. He does it to project an image that, even if sincere, carries the faintest trace of dishonesty inherent in performance. If uppercase letters are try-hards, then lowercase writing is an attempt to appear unbothered—but it is still an attempt. Effortlessness is often achieved, like the no-makeup makeup routine or the eighty-dollar lived-in tee. A discerning eye sees the residue: the concealer flaking from the cheek, the price tag poking from the hem. It knows a writer elected to do without.

Perhaps the lowercase writer is not chasing cool, but is raging against the literary machine. “To hell with the rules!” the soft anarchist shouts, admiring the smallness of his sentences. But a true rebel focuses on the message, not the costume. Writing, as an art, with its thousand ways to resist and reimagine, does not need its tools to be dressed up or down.

Perhaps the lowercase writer is jaded and communicating emotional reserve similar to the cool writer. However, a tired person does not write at all. Writing is tedious work, not a habit for the depleted. Or perhaps lowercase suggests warmth and approachability—capital letters, with their tall and menacing stature, interfere with the writer’s cozy invitation to come as you are and stay awhile.

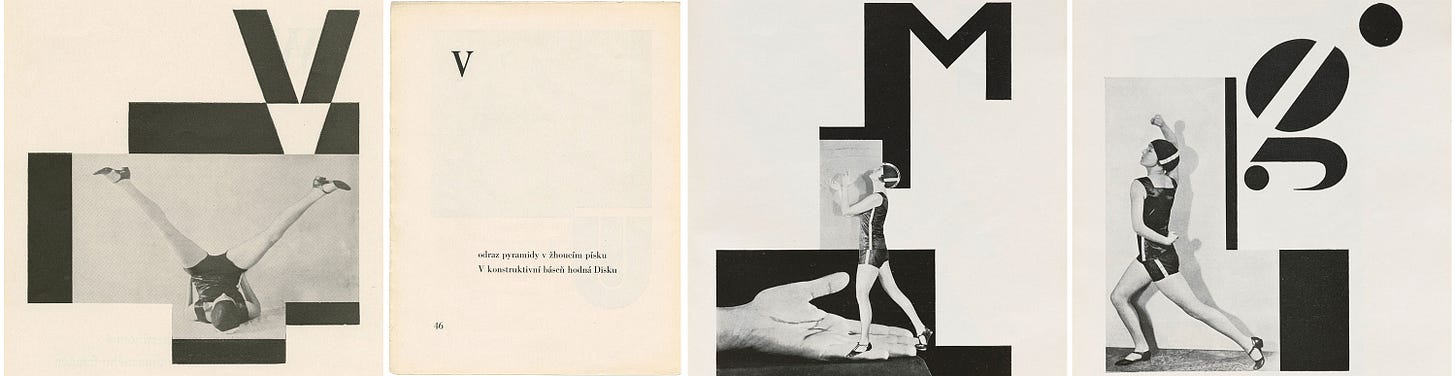

In the first half of the twentieth century, E.E. Cummings began writing in lowercase. He, too, wanted to subvert expectation and create a more resonant voice. Other avant garde poets and artists had experimented with typography before him, but it was Cummings who owned it. Scholars believe his “i” was meant to diminish ego, to visually represent the humility of self. What is more romantic than a humble man?

“i carry your heart with me (i carry it in my heart),” he wrote, famously.

In 1955, a student in Grand Rapids, Michigan wrote to Cummings to ask how to become a poet. He told them that a poet is someone who feels, and expresses those feelings through words. Anyone can learn to think or believe to know, he said. But the moment you feel, you are “nobody-but-yourself.” It’s the best defense of lowercase I’ve heard, mostly because it’s inarguable. If you feel like writing that way, go right ahead. But in present-day, Cummings—who valued authenticity above all else—might agree with me on this one: You are not uncapitalizing to free yourself. You are uncapitalizing to be liked, and that is not a worthy pursuit.